Looking for a shorter version?

A précis of the entire theory is included in chapter I.2.

The theory is also summarised in a blog post: The Meta-management Theory of Consciousness.

Got feedback?

I’d absolutely love to hear your feedback. Contact options are available from the About page.

Abstract

- Starting from first principles I develop a case for why consciousness evolved: to solve the meta-management problem of computational state trajectories in multi-iteration processing. I show that this is best solved through a meta-management feedback loop that presents a summary of computational state as an additional sense, enabling the first-order control process to meta-manage itself. I then explain how those mechanisms create the various phenomena associated with subjective experience: through the construction of Higher Order Observational States, a specific form of HOT. The “little person in the head” homunculus effect, the “stream of consciousness”, and the causal natures of consciousness all find a clear explanation. The theory shows how consciousness, intelligence, and meta-cognition are related, and paves a way towards human-level general intelligence.

Contents

- I.1 A Question of Consciousness

- I.2 Précis of Thesis

- I.3 Background - Consciousness

- I.4 Background - Biology and Neuroscience

Part II - Problems in Simple Synthetic Control Processes

- II.1 Interlude: Environment, Body, and Control Processes

- II.2 Complexity and the need for Processing Loops

- II.3 State Trajectories in a Multi-iteration Processor

Part III - Problems in Complex Synthetic Control Processes

- III.1 Meta-management in Deliberative Systems

- III.2 Interlude: Mechanisms of First-order Control Processes

- III.3 Interlude: Planning in AI and Biology

- III.4 Meta-control Options in Meta-management

- III.5 Meta-observation Options in Meta-Management

- III.6 Architectural Options for Meta-management

Part IV - Problems in Biological Control Processes

- IV.1 Embodiment

- IV.2 Interlude: Meta-cognition

- IV.3 Systems of Behavioural Control

- IV.4 Habitual and Rational Meta-management

- IV.5 Semiotics

- IV.6 Representations

- IV.7 Review of Meta-management

- V.1 The Architecture of Subjective Experience

- V.2 Subjective Experience States

- V.3 Interpretation of Subjective Experience States

- V.4 Explaining Phenomenology of Subjective Experience

- V.5 Conditions of Subjective Experience

- V.6 Degrees of Subjective Experience

- V.7 An example of an alternative consciousness

- VI.1 The Explanatory Gap and the Problem with Intuition

- VI.2 Argument By Elimination

- VI.3 Argument By Delusion

Part VII - Predictions and Conclusions

- VII.1 Convergence of Meta-Management

- VII.2 On the Causality of Consciousness

- VII.3 Comparison to other theories

- VII.4 Summary

- References

Part I - Introduction

I.1 A Question of Consciousness

It has been said that the field of neuroscience is data rich, and theory poor. While vast quantities of data are available from the nature of individual neurons to the activity of the brain as a whole, we lack functional theories of cognitive function in order to make sense of that data.

That problem is no less poignant for the question of consciousness. What is the basis of consciousness? It’s underlying mechanisms? What makes one thing conscious, while another is not? What is this ethereal “something other” that seems to be associated with conscious experience - the “what it feels like” to be conscious (Nagel, 1974)? We have ample information about so called correlates of consciousness - neurological data about high level brain activity at the time of conscious experience. But we lack an effective functional theory to compare that activity against. While many theories of consciousness (TOC) exist, they lack the details needed to sufficiently explain the neurological data.

I am interested in finding the mechanisms underlying conscious first-person subjective experience (subjective experience, hereafter), so that we can explain why those mechanisms and consequent subjective experience evolved, why subjective experience feels the way it does, and to explain the specific properties of subjective experience. This treatise seeks to do just that. Following a design stance that looks at the computational problems and solutions faced by increasingly complex artificial and biological organisms, I present a theory of both the computational and phenomenal aspects of subjective experience.

The theory presented is compatible with many existing theories of consciousness, including Higher-order Thought theories, Global Workspace Theory, and Integrated Information Theory. In fact, many of the ideas presented here are not new. But I believe this to be the most comprehensive attempt to ground those theories in a fundamental theory of why those mechanisms evolved in the first place. I suspect that in many respects, a key skill of anyone doing research in this area is to sieve through the many partial stories and see the path that links them together.

The immediately following chapter provides a concise summary of the theory from start to finish. This is followed by two background chapters, where the various terms used throughout are formally defined.

The rest of the treatise is divided into six additional parts. Parts II to IV examine the computational problems faced by increasingly complex embodied agents, along with a discussion of some of the solutions to those problems. Part V combines those discussions into a single coherent Solution and explains how that solution produces the properties of subjective experience. Part VI discusses how our intuitions produce the so called explanatory gap. Part VII completes the treatise with some discussion of further consequences of the theory and a final summary.

I.2 Précis of Thesis

I believe that three things go hand-in-hand: general intelligence, meta-management, and consciousness. Further, understanding these systems must proceed in that order. Thus, in order to understand why we have subjective experience, we need to begin to develop a theory of general intelligence and of the processes that restrain it from cascading into chaos. This treatise presents an end-to-end argument following that thread.

To save the impatient reader from the tedium of waiting till the end, the entire argument is first presented here in brief. Background explanations and some definitions are omitted for the sake of brevity. The rest of the treatise is devoted to detailed explanations of each of the logical steps in the argument thread here.

Any computational system is limited in the complexity that it can handle within a single execution of its computational process. For embodied agents, this appears as a limit on the environmental complexity that they can sufficiently model and respond to within a single executional iteration. For more complex problems, multiple iterations of processing are required in order to determine the next physical action. Such recurrency in processing may for example entail further analysis of the environment in order to better model its state; or consideration of alternative action plans. In biology, this provides scope for evolutionary pressures to trade off between a more energy hungry complex brain and a simpler less energy intensive one that takes longer to make some decisions (van Bergen & Kriegeskorte, 2020; Spoerer et al, 2020).

During the execution of a multi-iteration controller within an embodied agent, its control process (CP) passes through an internal state trajectory that is only occasionally associated with interaction with the physical environment. That internal state trajectory can become increasingly disassociated with the physical environment the more complex the problem space and the longer the time required for deliberation. If the multi-iteration processor must also learn through reinforcement then it is likely to exhibit chaotic and unproductive behaviour, particularly so during the earliest stages of learning. Reinforcement from the environment may be too sparse for efficient learning to take place, and simple rules that penalise longer deliberation time may be insufficiently flexible to cater for the complexity of problem domains that the agent may be faced with. Explicit meta-management (second-order) processes are required to observe the first order control process, to model its behaviours, to track its success rate, to act upon it to prevent chaotic behaviours that could harm the agent, and to participate in providing rewards and penalties with more advanced problem-domain aware knowledge than just a simple penalty for deliberation time.

In a complex biological brain that can operate its body effectively within the real world, including all the complexity of modern human life, the systems and processes required to model and understand the environment and to interact with them are immense. It turns out that the systems required to effectively carry out meta-management are similarly complex. More importantly, the kinds of systems required for meta-management are similar to those required for first-order control: observing, modelling, inference, planning, sequencing, controlling. Additionally, in order to effectively meta-manage the first-order control process, the domain knowledge required by the meta-management process is often strongly associated with the domain knowledge employed by the first-order control process at the time. The level of overlap between first-order control and meta-management implies a radical solution: that the first-order control process meta-manages itself.

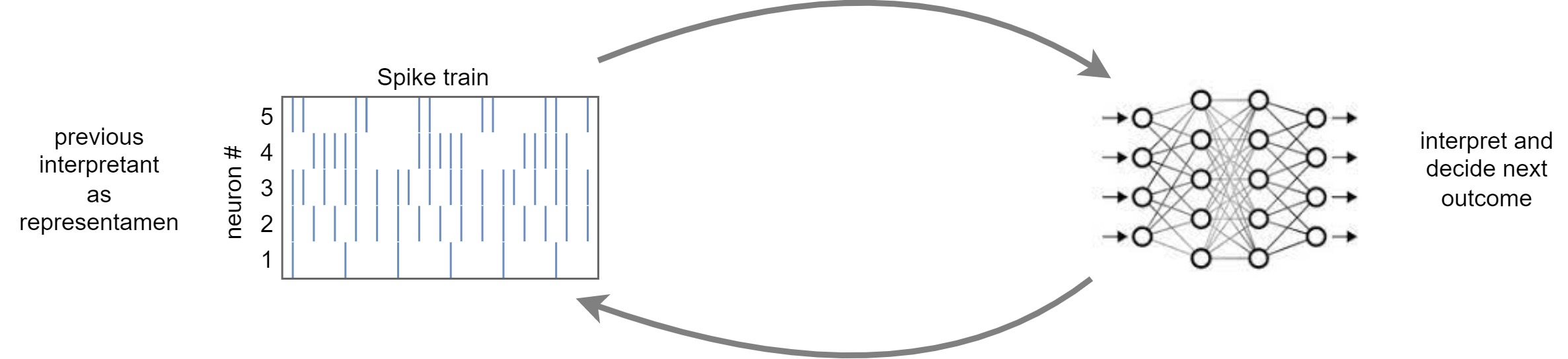

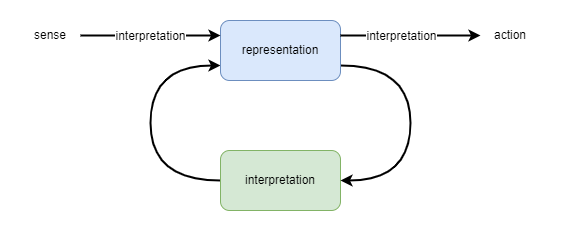

In order to meta-manage itself, the control process needs to observe itself. This can be achieved through a meta-management feedback loop that observes the state of the control process, observes the recent trajectory of the control process, distils that into a high-level abstract representation with lower dimensionality, and makes it available to the control process as a sensory input signal. Thus, the fact that we have awareness of some aspects of our own mental state is a direct result of the need for meta-management. In other words, the meta-management feedback loop is an additional perceptual sense.

The existence of the meta-management feedback loop does not alone explain subjective experience. Two more ingredients are required: interpretation and meaning. In a complex organism such as a human being, the brain maintains schema that represent and track the characteristics of different aspects of the individual. This includes the body schema, which models and tracks the location and orientation of the limbs, their abilities, and whether any injuries have been acquired. This includes schema about regularly encountered external things, such as is required to mentally track the location and orientation of the wheels while driving a car over potholes. With the introduction of the meta-management feedback loop, this also includes schema for tracking the state and capabilities of the cognitive processes. And, importantly, it includes a strongly developed sense of self vs other. All external and internal sensory inputs (including the meta-management feedback loop), all schema states, are labelled as to their source. Different source labels imply significantly different meaning in terms of, for example, the level to which the agent can affect that state.

External sensory inputs, meaning association, and feedback loop together are interpreted by the brain and a decision made about the next action. Information about that action and/or the mental state that produced it is available via the feedback loop in the next iteration of processing. This creates a continuous cyclic stream of ever changing inputs, states and actions. As the control process decides to perform some body action, knowledge of that chosen action is immediately available as a sensory input before the action is even started. As the control process chooses to deliberate further on a problem at hand, knowledge of that deliberation is immediately available. At every moment in time, the control process can choose to attend to external matters, to the continuation of the current deliberation problem at hand, or to the very feedback sense that it receives continuously while it is usually distracted doing other things. If the control process stops to consider its own feedback sense, compares that to memory of recent deliberations, compares that to its schema of self vs other, it necessarily concludes that it has its own “stream of thought”. That stream of thought is subjective experience.

The metaphor of a philosophical zombie was introduced to hypothesise a human-like individual that has all the behavioural characteristics of a human, including voicing that it is conscious, without actually experiencing subjective experience. A philosophical zombie is behaviourally indistinguishable from a human with consciousness. I argue that, if the zombie employs the mechanisms given in the explanation above (and outlined in more detail in the chapters that follow), then it is also computationally indistinguishable from a human with consciousness. In other words, if we were to assume an ability to tap into all of the inner state and workings of a brain, and if we were to compare the philosophical zombie from the conscious human, we would find no difference. At that point I argue that the zombie is not a zombie after all, but instead is a fully conscious human being having subjective experience.

Finally, I argue that our disgruntlement with such an explanation is not an explanatory gap (Levine, 1983; Van Gulick, 2022), but an intuitional gap. Nagel famously pointed out that we have no conception of what it is like to be anything other than ourselves (Nagel, 1974), and Block argued further that we have “no conception of a ground of rational belief” that could enable us to develop such a conception, or even to know whether or not something unlike a human is conscious (Block, 2002, p. 408). But that does not stop us making assumptions about what things should and should not experience subjective experience. It took science a long time to accept that animals could have any form of consciousness and subjective experience, and likely many still deny that outcome. If we have no way to conceive of the experience held by an animal, why should we be so adamant about its properties? The answer simply is our deluded intuition. Our brains excel at finding patterns and extrapolating from them. This works well when the physical environment around us is there to provide an error signal. But when no error signal is available, we are prone to delusion. Our minds create such a strong sense of self vs other by keying that information into every sensory signal that we ever receive, so that our senses seem to take on an extra quality of realness, of subjectiveness, of qualia (Tye, 2021). That seeming extra quality is further processed by the same system that produced it, reinforcing the delusion that the qualia is something extra, beyond mere sensory information. And thus we are deluded into the intuition that subjective experience is somehow more than can be produced by mere computational processing.

I.3 Background - Consciousness

Many theories exist about the nature of consciousness. A very brief summary of such theories will be given here. This serves two purposes. Firstly, to provide a background to readers who are not familiar with the topic. Secondly, to define clearly the particular meanings that I will use for various key terms throughout the rest of the treatise.

The word “consciousness” is an overloaded term, ie: that it has many meanings, with the particular meaning depending on context. Furthermore, consciousness of the sort that I wish to talk about here is an ill-defined concept. For example, consider the following working definition:

By consciousness I simply mean those subjective states of awareness or sentience that begin when one wakes in the morning and continue throughout the period that one is awake until one falls into a dreamless sleep, into a coma, or dies or is otherwise, as they say, unconscious. (Searle, 1990)

Firstly, this is not a definition, but an example. One that implores the reader to refer to their own intuition in order to guess the author’s meaning. But this is typical of any research in this field, and I shall do no better. Secondly, the example leaves ambiguous the case of dreams, which many might argue also carry some extent of conscious-like awareness.

Here is my own attempt at defining consciousness of the form that shall be discussed within this treatise:

- Consciousness is the collection of first-person subjective experiences that we have, for example, while awake. Not only do we have such experiences, but we can be aware of the fact that we are having or have had those experiences. We also have first-person subjective experiences while dreaming, and thus consciousness refers to those experiences too. In contrast, consciousness is absent when in deep sleep, and presumably when in vegetative comas. Likewise we are not conscious of everything that happens in our brain, even at the best of times. For example, when you look across the room and observe a chair, you have no awareness of any of the processes that just occurred within the brain that took the visual sensory information and identified that a chair was present. So, consciousness includes the things that you aware of, and excludes those things that you are not aware of.

Unfortunately there is still much ambiguity and room for disagreement. But it will suffice as a start so that I can refine some ideas as we go along.

I.3.1 Questions of Consciousness

For the study of consciousness, we have three broad questions that we wish to answer, that can be paraphrased as “what, why and how?”:

- What: what are the defining characteristics and properties of consciousness? ie: what do we look for in order to identify whether some thing or some creature experiences consciousness, or to distinguish whether a particular mental state is conscious? Also, what kinds of properties are we trying to explain through an explanation of consciousness?

- Why: why does it exist? ie: why did it evolve? What functional benefit does it offer over and above a creature that lacks consciousness?

- How: how does it occur? ie: what are the underlying mechanisms that produce consciousness?

The definitions given above are examples of attempts to answer the “what” question, but there are many more details yet to be elaborated on.

The “what, why, and how” questions can be focused on two different scopes:

- Creature Consciousness: what is it about certain things (humans, animals, maybe other kinds of things) that results in them having consciousness, while other things do not?

- State Consciousness: what is it about certain brain states that mean that the individual has conscious experience of those states, while not having conscious experience of other states? And which aspects of those states are associated with consciousness?

For example, this leads to different variants of the “what” question, two of which are a) what are the characteristics associated with creature consciousness? b) what kinds of things are we conscious of?

A good answer to the former requires us to answer the questions of why and how. But the latter is more open to investigation on its own. A few kinds of experience have been identified:

- Perception: specifically via the traditional five senses of sight, sound, smell, taste, touch that give us information about the world external to us (Gleitman, 2004, p. 204-237)

- Bodily awareness: this includes strong feelings such as pains and pleasures, and more subtle body-state awareness such as balance and proprioception (de Vignemont, 2020; Bermúdez, 2005; Mandrigin, 2021)

- Memory: recalling past experiences, where that past experience may be any of the sorts described here (Gleitman, 2004, p. 242-273)

- Imagination: conjuring images (and perhaps via other modalities) within our mind of things that do not exist (Liao and Gendler, 2020)

- Emotion: the experience of feeling one’s emotional state (Scarantino and de Sousa, 2021)

- Desire: the awareness of ones goals and desires (Smithies and Weiss, 2019; Schroeder, 2020)

- Action: experience and awareness of one’s actions, or of the intent to act (Tsakiris and Haggard, 2005; Bayne and Pacherie, 2007)

- Thought: an awareness of the sequence of thoughts, such as during problem solving, including but not limited to internal imagined worded vocalisations (Gleitman, 2004, p. 278-315)

The term “experience” itself is sometimes attributed to only a subset of the above, but I shall use it here to refer to any of the above where one could be said as being consciously aware of that experience. Or in other words, I take it that we can consciously experience all of the above “experiences”.

We can also ask what it is about experiences that make them somehow special. Again an appeal to intuition is necessary. If a modern computer can produce interesting behaviour but we take it as granted that it has no conscious experience, and in fact nothing we would even call “experience” of any sort, then what are the properties of experience that are lacking in the computer? Another example uses a so called philosophical zombie (or p-zombie for short), which is identical to a conscious human in every respect except that they have no conscious experience (Chalmers, 1996). In particular, they behave in every way like a human including having all the same conversations as a human, but all of their behaviour is produced in some way more comparable to the modern computer - there is “no light on upstairs”. We can say that the states of both the human mind and p-zombie include everything they need to include in order to produce behaviour, but that the state of the human mind also includes properties of experience that are lacking in the p-zombie.

These properties are the phenomological properties of experience, also known as qualia (Tye, 2021). Frustratingly, it has been painfully difficult to pin down these properties. They are often summarised simply as the “what it’s like” to have experience (Nagel, 1974) or the “raw feels” of consciousness. Another problem with discussions of qualia is that such discussions often get caught up with the observation that perceptions don’t always correlate exactly with reality; a case that is seen clearly with the way that our perception of colour of a particular object is only tenuously associated with the physics of light and its interactions with that object. How our perception correlates or fails to correlate with reality is an important question, and not entirely unrelated to the former question, but it is somewhat of a distraction when we are trying to define what qualia are in the first place.

One such property is that experiences seem to “look through” to the content of the underlying perception etc. that is being experienced (Siewert, 2004). While many debates exist, we seemingly always have experiences of something (Siegel, 2021; Siewert 2022). The something that experience is of is referred to as the intent of the experience (Crane, 2009). The word “intent” here does not take its usual English meaning; rather, it is best thought of as a target or a focus. A noticeable feature of experiential intent is that it is relatively easy to conceive that it could be constructed through entirely mechanistic processes. That stands in stark contrast to the experience itself. Other properties that could perhaps be associated with experience itself include the individual’s awareness of themself, and a sense of agency or purpose (Smith, 2018).

A problem that arises is whether the experience of intent and the intent itself can be separated. This has led some to consider a conceptual separation, and perhaps even an actual separation, between the following (Block, 1995):

- Access Consciousness: awareness of the perception, body sensation, memory, imagination, emotion, desire, action, or thought, to a sufficient extent that the individual can in some way react to the experience

- Phenomenal Consciousness: the first-person subjective experience of those things.

For the most part these two forms of consciousness are tied together. Most would view access consciousness as excluding non-conscious processes by definition. In other words, access consciousness is restricted to awareness of experiences that have a phenomenal nature. Likewise, phenomenal consciousness has a content, and that content is usually what we refer to as access consciousness. But many debates exist, resting on more detailed analysis and on attempts to define these terms more accurately. For example, there are claims that some phenomenal conscious experiences carry no representational qualities of the sort that characterise access consciousness, and thus that it may be possible to have phenomenal consciousness without access consciousness (Block, 1995). Likewise, some definitions of access consciousness make it possible to have access consciousness without phenomenal consciousness.

I subscribe to the view that access consciousness and phenomenal consciousness are just different ways of looking at the same thing. Specifically, that access consciousness is a reference to the processes that construct the specific content of consciousness, including not just the intent but also its “raw feels”, while phenomenal consciousness is a reference to the question of why that specific content became conscious in the first place. Mind you, this is not a standard view; most would associate the raw feels with phenomenal consciousness as something that is somehow distinguishable from access consciousness. It is for this reason that I predominantly use the term subjective experience throughout this treatise, instead of consciousness. I wish to be clear that my theory is about both access and phenomenal consciousness (as per Block’s definitions), together as a single thing.

I.3.2 The Purpose of Consciousness

Why does consciousness exist? Presumably conscious experience confers some sort of benefit to the individual in order that it evolved. In order words, we assume that it serves some function or functions, that those functions are useful, and that the individual would be at a disadvantage if it were lacking those functions.

When attempting to decipher the function of consciousness, there are a number of different angles that should be considered (Niikawa et al, 2020; Rosenthal, 2008). Firstly, we need to distinguish whether we are asking about creature consciousness or state consciousness. On the one hand, we’re asking whether the creature as a whole benefits from having conscious experience. On the other hand, we are asking whether a given process benefits from having conscious experience associated with part or the whole of that process.

A second important consideration is to distinguish whether we are talking about the functional basis of consciousness, or the functional contribution of consciousness (Niikawa et al, 2020). As we now understand, many brain processes occur unconsciously, including many processes that are associated with perceptions and thoughts that we consciously experience (Earl, 2014). The functional basis of consciousness is an otherwise unconscious process that produces conscious experience. In contrast, the functional contribution of consciousness is the effect that conscious experience itself produces - it is whatever behaviour or other function that conscious experience bestows upon the individual and that they would not otherwise have had.

Unfortunately, when we understand so little about the processes underlying consciousness, it can be very hard to tease those two conceptions apart. Thus most work that attempts to pinpoint a purpose for consciousness could be said more accurately to identify a correlation and to then build up a theory around that correlation.

A number of such theories have been proposed that either attempt to directly suggest a functional purpose for consciousness, or that merely suggest a possible purpose as part of larger theories into the what or how of consciousness. Some broad ideas follow.

Integration and Global broadcast: a predominant feature of consciousness is that it appears to pull together multiple streams of information into a single coherent representation and than make that available for further processing by other systems. This is held as the key purpose of consciousness within a number of theories, including Global (Neuronal) Workspace Theory (Baars and Franklin, 2007; Dehaene et al, 2003; Dehaene, 2014), IIT (Tononi and Sporns, 2003), and Supramodular Interaction Theory (Morsella, 2005).

Flexible behaviour: another predominant feature of consciousness is its apparent association with flexible behaviour. This can be characterised as an ability to adapt to novel situations more rapidly than would be expected from experimental “learning” alone. A closely related and somewhat ill-defined conception is that of “rational behaviour”. Many have proposed that consciousness serves to enable adaptive and/or rational behaviour (Kotchoubey, 2018; Morsella, 2005; Earl, 2014; Humphrey, 2002; Shimamura, 2000; Tye, 1996).

Counter-factual reasoning: Some have proposed that consciousness enables flexible and adaptive behaviour through specific mechanisms. One such example is that of enabling counter-factual reasoning through the ability to imagine alternatives (Kanai et al, 2019).

Association learning: Another specific case of flexible behaviour is through the ability to learn a seemingly unlimited range of associations, both from direct experience and from second hand experience such as observing others or being told about the association. It has been suggested that consciousness directly correlates with that ability and thus must be an integral part of the ability (Birch et al, 2020).

Meta-cognition: A view that some have taken, this author included, is that consciousness is strongly associated with meta-cognition (Fernandez Cruz et al, 2016; Paul et al, 2015; Flemming et al, 2014; Flemming et al, 2012; Cleeremans, 2007; Shimamura, 2000). For example, perhaps the point of the integration and broadcasting associated with consciousness is to obtain enough information to enable the individual to determine how best to gain more information (Kriegel, 2004). Or perhaps it is for the detection and correction of errors encountered when performing long chains of reasoning (Rolls, 2004 and 2005).

Social interactions: A fascinating possibility is that consciousness evolved as an integral part of our nature as a social species. Consciousness enables theory of mind about one’s own mind, and by extension, the minds of others (Frith, 2008; Bahrami et al, 2012; Flemming et al, 2012). Theory of mind plays a key part in enabling us to cooperate with other individuals.

Volition: Consciousness may simply be the magic ingredient that enables mobile bundles of matter to have volition in a free-will sense (Pierson and Trout, 2017). For example, Panpsychism holds that consciousness is a fundamental property of the universe (Chalmers, 1996), and of all the matter within it. A commonly presumed feature of such panpsychist consciousness is that it has free-will, and thus it would confer free-will onto the behaviour of individuals.

Functionless: Another possibility is that consciousness confers no benefit to the individual. For example, this is implied by the claims of Epiphenomenalism (Robinson, 2019). A slightly softer stance is that consciousness occurs as a side effect of other functions, where those functions themselves provide significant benefit to the individual, but consciousness itself does not add any extra benefit (Rosenthal, 2008). Under this view, consciousness is a side-effect of behaviour rather than a driver of behaviour.

Other supposed purposes of consciousness identify strong correlations but fail to explain why consciousness is needed for that to occur. For example, consciousness appears to be essential for long-term episodic memory; we are unable to remember things that we were not conscious of at the time (Tulving, 1987; Edelman et al, 2011).

I.3.3 General Theories of Consciousness

I now describe some generic and specific theories of consciousness. To provide some grounding to the summary and to aid in comparing theories, a framework of a stack of conceptual layers is used, illustrated in the diagram that follows. This is not meant to imply a priori anything about the actual structure of consciousness and its underlying mechanisms. For example, none of the layers are assumed necessarily to exist a priori, nor is the particular illustrated order appropriate in every case.

- Conceptual layers used here to summarise theories of consciousness. Substrate: the physical biology of the brain is viewed as a substrate that “hosts” other processes, such as computational processes. In some theories the substrate might potentially be replaced or emulated via some other substrate (eg: silicon neurons). A-conscious processes: all processes built upon the particular substrate (eg: neural signalling) that produce behaviour and/or affect the state of the brain. Some of these processes or their results are somehow associated with conscious experience, while others are not. Representation: some theories hold that particular kinds of representations are associated with conscious experience. Functional Structures: some theories hold that certain kinds of structure are key to conscious experience. Something Special: some claim that conscious experience is an effect that cannot be explained via purely materialistic means, or that we need some new kind of understanding to explain it. Subjective Experience: the ultimate effect of consciousness that we wish to understand.

The substrate is the (generally physical) thing in which the processes of the mind are carried out. For example, biology and neuroscience has taught us that biological neurons are the substrate of the human mind. There is a conceptual difference between the thing that “hosts” the processes, and the processes themselves. Historically there has been three broad views with regards to the substrate. Perhaps the oldest view is the dualist view of Descartes. In their view there was the physical substrate, entailing the body and brain, and there was some other non-physical substance that hosted the mind, independent of the physical body (Descartes, 1911; Van Gulick, 2022). While few hold to that view today, it made more sense at the time when Descartes first proposed it. Reportedly Aristotle believed that the purpose of the brain was to cool the blood (Smart, 2022). Many today hold to a monist view that there is only one substrate, and that this substrate is physical, for example the biological neurons of the brain. More generally, such physicalistic or materialistic views hold that the properties of physical substances and their interactions are entirely sufficient from which to base an explanation of everything about consciousness, even if we don’t know enough about those properties just yet (Stoljar, 2023). An alternative monist view, that of idealism, is that nothing is physical and that everything we perceive exists only within our minds (Guyer and Horstmann, 2023).

Returning to the materialistic view, for humans and for any other animal that happens to have consciousness, we can say that the conscious mind is realized upon the physical substrate of biological neurons. Is that the only physical substrate upon which consciousness can be realized? If consciousness is multi-realizable then perhaps it could also be realized upon silicon neurons. Even more radically, perhaps the operation of neurons could be simulated within a super computer, and a simulated brain could also by conscious. By extension, if multi-realizability is true, then any functional isomorphism of a biological human brain should be not only conscious, but conscious in a human-like way. In contrast, psycho-physical identity theory posits that there may be something special about biological neurons that give rise to subjective experience, and that non-biological functional isomorphisms would not have such experiences (Van Gulick, 2022).

One view of brain activity is that it is computational in nature (Rescorla, 2020). Initial versions of this idea likened such computation to that of the Turing machine (McCulloch and Pitts, 1943), with its serial computation, finite set of states, and random access memory. Later variations accepted that the brain wasn’t exactly like a Turing machine, but was still Turing-like. In particular, Turing machines operate upon a finite set of symbols. Fodor’s representational theory of mind (Fodor, 1975, 1981, 1987, 1990, 1994 and 2008) extended that idea to more generic representations. Importantly, these representations could be hierarchically composed, enabling their computational model to create infinitely many variations of states, more closely mirroring our ability to form larger ideas by composition of smaller ones. Nowadays, most apply a connectionist lens to computation (Marcus, 2001; Smolensky, 1988; Kriegesgorte, 2015), following advances in both our neuroscientific understanding of the brain and in artificial intelligence (Krizhevsky, Sutskever, and Hinton, 2012; LeCun, Bengio, and Hinton, 2015). Another lens recognises that the brain must deal with a significant amount of uncertainty and thus might actively include that within its representations and computations (Ma, 2019; Rescorla, 2019).

One particular line of criticism levelled at computational models draws issue with the idea of representation (Rescorla, 2020). Initial views of the brain as a Turing machine, or at least Turing-like, suggested that the brain would operate against symbols in the same way that a computer does. This drew obvious criticism. But the modern connectionist view of computation is not immune. One particularly strong issue lies with the distinction between syntax and semantics. Here, syntax refers just to the form of the representation, while semantics refers to its meaning. A clear example of the distinction can be seen in the case of computers. In a modern computer, all information is represented via the form of zeros and ones, regardless of its meaning. For example, a particular string of zeros and ones might mean a particular base-10 number, or it might mean the colour of a pixel. Furthermore, all computation is performed against the syntactic form alone. This can be seen in the way that two large base-10 numbers can be multiplied by a mechanistic process that lacks any knowledge that it is multiplying base-10 numbers. It sees only a sequence of binary bits and performs only a series of simple per-bit operations (Booth, 1951) that do not involve any multiplication. There exist arguments that all computation is of this form (Rescorla, 2020), including that of the brain (Fodor, 1981). It is intuitively problematic that the inherent meaning of the representation is discarded, and thus there is a reluctance to accept representation as being a complete story of mind.

My own stance is that meaning is not lost. For simple habitually repeated operations it is encoded within the process that performs the computation, and for complex operations the meaning is itself represented. But more on that later.

It is now known that many brain processes operate that neither directly nor indirectly lead to any kind of subjective experience [citation]. And for those processes that do have an impact on subjective experience, the vast majority of the details of those processes are still hidden from that subjective experience, including the operation of the processes and the content that they operate on (Nisbett and Wilson, 1977a). While earlier work assumed that most brain processes are conscious, there is increasingly strong evidence in fact that almost all mental processes are non-conscious, even for mental processes that are associated with attentive subjective experience [citation].

An obvious question thus arises about why certain processes and/or representations would be associated with subjective experience and others would not. Is it sufficient that a particular kind of representation exists for it to be associated with subjective experience, or does that representation need to occur in conjunction with particular functional structures? For example, imagine that all aspects of the brain were understood to the point that we could identify exactly which representations are associated with subjective experience. Now imagine that an exact replica of a particular representation was encoded within the gates of a silicon memory chip within a computer. Most would argue that the silicon memory chip does not subsequently have subjective experience of that representation, because a representational state alone is insufficient for subjective experience. Some kind of functional structure presumably must be required to observe that representation. But if functional structures are indeed required, what are those functional structures? And what distinguishes those functional structures that are associated with subjective experience and those that are not?

A deeper philosophical question exists about whether representation and functional structures alone are sufficient to produce subjective experience, or whether something else is required. A representational state is just a state. It doesn’t do anything. So it can’t be the source of subjective experience. But a functional structure is just static (biological) machinery. More clearly, while the functional structure may change as the result of learning, at the moment that it produces any given behaviour its structure is static. So that couldn’t produce subjective experience either. Thus perhaps qualia is a case of an extra something special that we do not yet understand about physics, or that exists in a dualistic relationship to physics. These are the questions posed by the distinction between access consciousness and phenomenal consciousness. Consider this example provided by the Britannica online article on philosophy of mind:

Suppose that, in order to avoid the risks to his patient of anaesthesia, a resourceful surgeon finds a way of temporarily depriving the patient of whatever nonfunctional condition the critic of functionalism insists on, while keeping the functional organization of the patient’s brain intact. As the surgeon proceeds with, say, a massive abdominal operation, the patient’s functional organization might lead him to think that he is in acute pain and to very much prefer that he not be, even though the surgeon assures him that he could not be in pain because he has been deprived of precisely “what it takes.” It is hard to believe that even the most ardent qualiaphile would be satisfied by such assurances.

If all the representational and functional structures are in place for an individual to have both the external behaviours and internal mental behaviours of an individual in intense pain, can we even conceive it to be possible that they would not have the typical associated subjective experience of the pain?

I.3.4 Specific Theories of Consciousness

Higher-order Thought (HOT) and Higher-order Perception (HOP) are a group of theories that focus on the form of the representation. It is claimed that there are broadly two types of cognitive state (Carruthers and and Gennaro, 2020; Rosenthal, 2004). First-order states are the primary states of the brain involved with control of behaviour in the absence of subjective experience, such as visual and auditory information about the outside world. In contrast, higher-order states represent things about those first-order states.

Where a higher-order state represents that a first-order state was experienced, then we have conscious experience. Several variations exist in this group of theories. HOP theories focus on perception, and in particular an idea that we have an explicit perceptual inner-sense that observes our cognitive state, for example in the same way that our visual sense observes the world outside (Armstrong, 1994; Armstrong & Malcolm, 1984; Lycan, 1996 and 2004). HOT theories are computational theories that propose that higher-order states are constructed from or about the first-order states. Some HOT theories propose that first-order states become conscious through the presence of associated higher-order states, and thus that we only experience such first-order states at the moment that a HOT in constructed about them (Rosenthal, 1986, 1993, and 2005). A subtle variation holds that certain first-order states are inherently disposed to have associated higher-order states and that that is sufficient for the first-order states to be experienced as conscious (Carruthers, 1996, 2000, and 2005). Some view that first-order states and higher-order states are related but independent, and thus that one kind can occur without the other, while others take a self-representational view that higher-order states are somehow always constructed inline with their intentional first-order states (Gennaro, 1996 and 2012; Kriegel, 2003, 2006 and 2009).

Global Workspace Theory (GWT) sees the brain as a system of individual computational processes that compete, and sometimes collaborate, to gain a winner(s)-take-all right to broadcast their results to a global workspace (Baars, 2021; Baars and Franklin, 2007). The state of the global workspace then forms the context upon which subsequent processing occurs by all those same computational processes. This occurs in a continuous and dynamic way typical of the parallel processing that we’ve come to understand about the brain. GWT is primarily a theory of cognitive processing that focuses on its a-conscious processes, representations, and functional structures. In doing so it offers a partial explanation of the underlying mechanisms of rational thought, or so called general intelligence. The link to subjective experience is by way of claiming that the global workspace is the content of subjective experience, based on correlations with the apparent integrative nature of conscious perceptual attention and decision making, forming an apparent single stream of consciousness (Baars, 2021). GWT is an abstract computational theory that composes high-level concepts such as a workspace, processes, frames, and competition and collaboration between processes. While it makes some claims about regions of brain involved, it doesn’t explain how groups of neurons produce such behaviour. In other words, it omits important details about the substrate from its explanation.

GNT was formed by Baars (1988), but has been taken up and extended by many others, such as to provide a more detailed computational model (Franklin and Graesser, 1999), the addition of internal simulation (Shanahan, 2005), or to model via spiking neurons (Shanahan, 2008). Of particular note is Global Neuronal Workspace theory (GNW). GNW takes inspiration from a growing view of neuronal interactions as dynamical systems (Miller, 2016; Favela, 2020; Shapiro, 2013). It proposes how non-linear interactions between populations of neurons can create a sudden “ignition” effect, where multiple independent stimuli suddenly become mutually salient, particularly due to long-range axons from sensorial stimuli (Dehaene, Sergent, and Changeux, 2003). In other words, it proposes a specific mechanism of how groups of neurons can cooperate to form a single representation that is then broadcast to others.

The massive number of neurons within the substrate of the brain makes it hard to study how specific computational theories may or may not apply, both from the point of view of empirical neurological investigations and in analytical attempts to formulate how neurons interact to form those higher-level computational abstractions. One avenue is to embrace the combinatorial complexity and to examine the activity across populations of neurons - ie: groups of neurons that are spatially close and/or are activate together in some sense. This is seen in theories that view the brain as a dynamical system, mentioned earlier, use information theoretic techniques, or that look at waves and oscillations in the pattern of activity.

The work on the Theory of Neuronal Group Selection (TNGS) (Edelman 1987; Edelman 2003), also known as Neural Darwinism, provides one such example. As part of developing TNGS, the authors developed the Dynamic Core hypothesis (Edelman and Tononi 2000; Tononi and Edelman 1998), which provides a quantitive measure of neural complexity (Tononi et al, 1994). The measure is based on the information theoretic idea of mutual information. Consider two random variables x, and y. If knowing the value of x informs me of anything about y, then we say that they have mutual information. The more x and y correlate, the more mutual information there is between them. In contrast, if they are statistically independent, then they carry zero mutual information. Mutual information is important if you care about finding correlations or relationships between things (more mutual information is good), and if you care about being able to store or represent large amounts of detail (less mutual information is good). Within the brain there will be regions of activity that are differentiated: to a large extent uncorrelated perhaps because they are busy with different functions, or perhaps because the brain is in a state of disorganised chaos. Likewise there will be regions of activity that are integrated: strongly correlated because for example that the brain is organised and focused on one task, or perhaps because it has a lot of unnecessary duplication. Neural complexity measures the extent to which activity within the network is both integrated and differentiated by computing the average mutual information between bipartitions of the network.

Integrated Information Theory (IIT) provides another closely related measure that claims to calculate an objective quantity of consciousness, indicated as Φ (phi). This looks not just for mutual information, which is inherently bidirectional (ie: just a correlation without any idea of cause-effect relationships), but attempts to measure the extent to which certain information is causually effective. It then computes the amount of causally effective information that can be integrated across the weakest link of the the system (Tononi and Sporns, 2003; Tononi, 2004). This has since received two major revisions, first in 2008 to measure based on active dynamics rather than static configuration (Tononi, 2008), and then again in 2014 with the introduction of maximally irreducible conceptual structures (MICS) (Oizumi, Albantakis, and Tononi, 2014).

Another approach is to look at the dynamics of waves and oscillations of activity within the brain. For example, in older studies it was found that consciousness coincided with so called gamma-waves, in the frequency range 30 to 80 Hz, in electroencephalogram (EEG) readings. That is now understood as being the outwardly measurable effect of the micro-interactions at the neuronal level (Llinás, Ribary, Contreras & Pedroarena, 1998; Friston et al 2014; Hunt and Schooler, 2019). In particular, a productive line of thought has been to treat such brain activity as harmonics, with different global and sub-global populations of neurons dynamically forming groups of closely synchronised activity (Atasoy, Donnelly, and Pearson, 2016; Atasoy et al 2018). The ever changing groupings of neurons that create those harmonics is proposed to be self-organising, with one theory describing self-organizing harmonic modes (SOHMs) (Safron, 2020). The larger Integrated World Modeling Theory of consciousness (IWMT) (Safron, 2020), where SOHMs were introduced, combines IIT and GNW with the Free Energy Principle (Friston, 2019) and Active Inference Framework of Friston (Friston, Kilner, and Harrison, 2006; Friston et al 2017; Sajid et al 2021).

It is important to note that while such theories find useful correlations to consciousness, known as neural correlates of consciousness (NCC), they may not explain the mechanism by which those correlated activities or measures produce subjective experience.

Other noteworthy theories include the Orch OR theory of consciousness (Hameroff & Penrose, 1996a, 1996b, 2014; Hameroff, 2021), and pan-psychism (Chalmers, 2013; Goff, Seager & Allen-Hermanson, 2022).

I.3.5 More Reading

For those who wish to learn more, the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy has excellent articles covering many topics related to this area. In particular I recommend articles on: Consciousness, The Unity of Consciousness, The Contents of Perception, Perceptual Experience and Perceptual Justification, Representational Theories of Consciousness, The Computational Theory of Mind, Neuroscience of Consciousness, Higher-Order Theories of Consciousness, Introspection, Mental Causation, Epiphenomenalism, and Animal Consciousness. The Wikipedia article on Experience also provides an excellent summary of various concerns.

For more background on the various theories of consciousness, I recommend Seth (2022) and the Scholarpedia article on Models of Consciousness.

Many of the broad topics on consciousness require a background in philosophy to really understand them. For some readings, I recommend the Stanford Philosophy articles on Metaphysical Explanation, Phenomenology: 1. What is Phenomonology, Functionalism, and the Wikipedia article on Intentionality.

I.4 Background - Biology and Neuroscience

I shall not attempt to explain any of structure of the brain itself. However there is one important feature of the neurological aspect of brain function that needs to be described more fully, that of its dynamical systems nature. Many of the discussions later in this treatise combine simplistic functional descriptions with simple box-and-line diagrams using clearly demarked components. I want to dispel any misconceptions about the interpretation of those simplistic descriptions before they arise.

“Boxology” functional descriptions that, for example, include single individual boxes for processing and memory are simply wrong (Dennett, 1991, p. 271). The brain does not operate that way. Processing is a distributed product of many different systems (Vision: Spillmann et al, 2015; Livingstone and Hubel, 1987; Zeki and Shipp, 1988. Attention: Luo and Maunsell, 2019). Even memory may be a distributed effect, with a single memory actually being produced by different systems focused on the various different modalities that make up the memory (Postle, 2016; Carter et al, 2019, p. 156-159). However, simple functional descriptions give us something understandable to work with while we’re trying to figure out the broad ideas. Remapping that onto a dynamical systems substrate can come later.

Nevertheless, it will helpful to the reader to have some intuition of the brain’s true underlying dynamical systems nature. To that end, what follows is a brief description of one attempt at explanation, known as Predictive Coding.

I.4.1 The Predictive Coding theory of brain function

A traditional conception of brain processing of senses can be characterised as “perception by representation”: that the brain attempts to use the senses to accurately represent what is observed. A typical assumption associated with that characterisation is that sensory perception is a largely “feed-forward” process: raw low-level sensory signals are hierarchically interpreted into higher and higher-level representations, eventually identifying specific objects, their boundaries, and other properties such as location, pose, and motion (Buckley et al, 2017; Walsh et al 2020).

An alternative conception is characterised as “perception by inference”: that the brain attempts to infer the (hidden) state of the environment, known as the latent state, from sensory signals. In this conception, rather than predicting a representational model that correlates to the sensory signals, the brain attempts to model the underlying structure that caused the sensory signals (Friston, 2005). Furthermore, rather than producing this inference within a single forward pass, it is derived through an iterative process employing both feed-forward and feed-back signals (Rao and Ballard, 1999).

Predictive Coding is one such theory. It holds that much of brain function is the result of such inference (Friston, 2010; Clark, 2013 and 2019; Kilner, Friston, Frith, 2007), including not just perception but also action generation (Friston, 2010). The explanation stems from the observation that Bayesian inference is analytically intractable for most problems, but can be solved through the empirical bayes method by factorising the problem space (Buckley et al, 2017). A so called generative model, which models the the causal structure from environment state to sensory signal, can be approximated by factorising it in three ways (Buckley et al, 2017; Millidge, Seth, Buckley, 2021). Firstly, the state of the environment at a given moment in time can be factorised as a multi-variate combination of independent gaussians. Secondly, the time-dependent dynamics of state can be factorised into the current value, its first-order derivative, its second-order derivative, and so on. Thirdly, the unknown relationships between latent causes can be modelled and learned as a hierarchy of layers (Friston, 2008), with each successive layer acting as a generative model of the layer before.

This factorisation can be distributed across the neural structure of the cortex (Mumford, 1991; Rao and Ballard, 1999), with activity of each individual neuron representing the mean of the gaussian distribution of the particular variable that it models (Buckley et al, 2017), and possibly also representing the variance (Feldman, Friston, 2010). Some aspects of this 3-dimensional factorisation have already been identified within the structure and activity within the brain. For example, the hierarchical nature of brain processing can be seen in the way that the primary visual cortex processes visual information at a lower level of representation than the visual association area [citation], and similarly for the primary and secondary somatosensory areas (explained in Neuroscience Online, “Chapter 3: Motor Cortex”). Additionally, there is some evidence that neurons within the cortex are formed into columns, where the neurons in each column together model a single multi-dimensional variable (Mountcastle, 1997), likely modelling the full covariance matrix between those dimensions [citation].

- Predictive coding in action. A) Top-down computations predict sensory data based on high-level priors. Bottom-up computations indicate prediction errors, leading to updated priors. The process is repeated until prediction errors are sufficiently reduced. B) The same top-down and bottom-up interactions occur at the micro level between adjacent pairs of the hierarchical layers, and at the macro level across the entire system.

Counter-intuitively, under the theory of predictive coding, the forward computational direction from sensory signal to higher-level representation, also known as the bottom-up calculation, conveys only prediction error. The main computation is performed by the generative model during top-down computation, ie: in backward direction from high level representation towards low-level sensory input. Each layer within the hierarchy represents a prior on the layer below, conditioned on the layer above. At time of inference, bottom-up prediction error is used to identify priors that don’t fit reality, which triggers further prediction errors up to higher levels. That is eventually returned with new top-down conditioning adjusting the priors, ultimately resulting in each layer representing its best guess of the latent state at its level of representation. Over longer timescales, bottom-up prediction errors are also used to learn better generative models (Friston, 2008).

This leads to a lot of activity. A novel sensory signal is likely to immediately trigger prediction errors against priors in low-level layers that were framed by previous contextual information. Thus there is immediate short-range waves of generative prediction and prediction error activity (see panel B in the diagram above). In order to completely resolve the prediction errors, higher-level priors may need to be revised, resulting in long-range waves of activity (panel A in the diagram above). Activity eventually settles once prediction errors are sufficiently minimized across all layers.

Predictive coding offers an explanation of various otherwise puzzling features of perception (Millidge, Seth, Buckley, 2021), including so called “end-stopping” in visual perception, bistable perception effects under right/left-eye competition, repetition suppression, attentional modulation of neural activity, and of hebbian learning. The suitability of predictive coding as a larger theory of brain function is debated (Walsh et al 2020, and see commentaries on Clark, 2019), but the basic idea behind it may yet prove to be a good explanation of the waves of activity that we see in EEG and fRMI recordings.

Part II - Problems in Simple Synthetic Control Processes

This part and the two that follow it describe a series of problems that are faced by control processes, computational processes that control the behaviour of the larger system of which they are a component. This part is focused on simple artificial agents, while Part III is focused on more complex artificial agents. Part IV takes that up a notch to look at control processes in humans. Interspersed between chapters on control process problems are the occasional interlude chapter that provides additional background to the discussions immediately following.

II.1 Interlude: Environment, Body, and Control Processes

I shall start by defining some terminology and concepts.

While the latter sections and chapters of this treatise focus on human brain function, the earlier sections refer to agents in a more generic sense. Here I draw inspiration from artificial intelligence (AI) research, particularly from Reinforcement Learning (RL) settings (Schmidhuber, 2015; Lazaridis, 2020). In RL research, an agent may be nothing more than a computational device running on a computer that incorporates an artificial neural network (ANN) plus a hand-coded learning algorithm. The agent may be operated within a virtual environment, simulated within the same computer that executes the agents computations. Often the hand-coded learning algorithm has direct access to ground truth information (the true state of that virtual environment and the agent’s coordinates and state within that environment), whereas the agent has only specific simulated senses through which it must infer those states. In such a simulated environment, the agent may be embodied - having a (simulated/virtual) physical form; common examples include animal shape (eg: Eysenbach et al, 2019), cars (eg: Gosh et al, 2019), and robotic arms with a fixed base (eg: Nair et al, 2018; Colas et al, 2019; OpenAI, 2021). AI agents may also exist in the real world. Often in RL settings these are agents that are initially trained within a virtual environment that closely mimics the real world, and then the partially trained agent is transferred into the real world equivalent body. Humans and other animals can be considered as very complex natural biological agents. Many of the complex processes within the brains of humans have their origins in simpler organisms. Studying simple artificial agents is a first step towards understanding those processes.

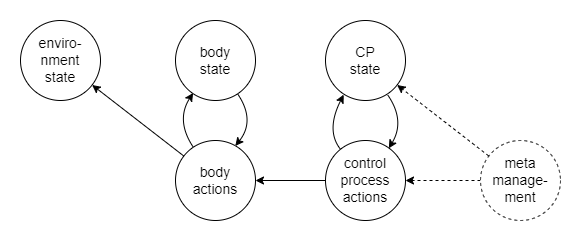

For an embodied agent that exists within an environment, there are three independent but interacting components at play: the environment, the body of the agent, and the agent’s collection of control processes (CPs). Illustrated in the following diagram.

- Relationships between environment, body, and control in an embodied agent. Body actions influence the state of the environment and of the body state, while body state influences how those body actions carry out. Environment state affects body state and motivates some of the body actions. Control processes observe body and environment state and govern the state of the body via body actions.

The environment is everything external to the agent, potentially including other agents. In simple synthetic AI settings, the environment is usually innocuous. In the real world it is highly dynamic and includes many dangers. The embodied agent that exists within the environment must monitor and predict the state of that environment so that it can a) benefit from the environment, b) modify the environment to meet its own needs, and c) avoid dangers inherent within the environment.

Within this treatise, body refers to the entire (real or virtual) physical form of the agent, including its outer surfaces and its internal structures and processes. The state of the body captures its externally visible components such as limbs, and its internal mechanical or biological processes such as those involved with homeostatic temperature regulation and energy production. Actions by the body include externally visible events such as moving a limb or producing audible communication, and internal processes such as those involved with temperature regulation and energy production. Body actions may be performed for the purpose of merely changing the body state, or they may be performed with the intent to change the environment (eg: put a plate on the table, or lift the object held by the robotic claw). There are three broad and somewhat overlapping reasons why the agent would perform body actions: i) to meet immediate homeostatic needs, ii) towards meeting a goal, and iii) exploration for the benefit of learning and gaining additional information that would be useful in the future.

For the sake of convenience of the discussions that follow we consider the control processes (CPs) of the agent as distinct from its body, particularly those that can be said as being computational in nature. In a typical AI agent, this refers to the entirety of its neural network(s) and/or other computational mechanisms of control and learning. In a biological organism such as humans, an approximation is to consider it as referring to the organism’s central and peripheral nervous system. A significant component of the control processes are required to monitor, predict, and to tune the body’s static state (eg: it’s current location and energy levels) and dynamic state (eg: speed and acceleration of limb movement, adapting to resistance in movement due to external or internal factors).

II.2 Complexity and the need for Processing Loops

In most artificial neural network (ANN) based reinforcement learning (RL) agents today, each input is associated with an immediately produced output. This means that in an embodied agent the choice of the next physical action is made by a single pass through its ANN(s): input nodes are populated with current sensory signals, matrix operations are carried out that permute and transform those input node values through the multi-layer network of weights, and the values produced by the output nodes are immediately taken as the chosen next action. This is true even for Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN). RNNs are recurrent in the sense that state from a previous pass is made available to influence the output on the next pass with the next input value. In this way, when a time-bound signal stream is fed into the RNN, it produces an output stream where each value in the output stream is influenced not just by the current input but by all inputs received up until that point. However, the RNN still produces exactly one output for every input, and each output is produced by a single pass through its network.

- Single-iteration Artificial Neural Networks (ANN). Each of these networks produce one output for each input, via a single pass pass through the network. In the context of an embodied agent, this means that the agent has no option for further deliberation of the same input.

Another form of recurrency is to execute multiple passes through the same network before producing an output. This form is common in hand-rolled algorithms, where it is usually referred to as processing loops. When an algorithm employs a processing loop, a single output may be produced for each input, but only after a variable length delay. Some inputs may lead to updates of internal algorithm state only, without producing an output. Or a single input may produce multiple outputs. Examples abound, but one familiar to those in the AI research community is the Expectation Maximisation algorithm. It takes as input a set of data points, produces as output a set of parameters that describes the input data set, and employs multiple iterations of alternating calculation of log-likelihood expectations and parameter optimisation. The alternating expectation and parameter optimisation loop is stopped according to a halting rule that is either based on detecting diminishing returns in the improvement of log likelihoods or on completing a fixed number of iterations.

Some have begun to experiment with loops in ANNs. Complex results can be achieved with shallower networks when using a loop-style of recurrency (Kubilius et al, 2019; Wen et al, 2018). Loop architectures have been used to adaptively vary the amount of computation time allocated to problems, as Adaptive Computation Time (Graves, 2016), which has been suggested as an important component of next generation language decoder-encoders known as Universal Translators (Dehghani et al, 2018).

There is a practical limit to the complexity that a single-iteration processing architecture can achieve. The network can be made broader (more nodes in each layer) and deeper (more layers), but that increases the number of parameters that need to be optimised during learning. In earlier versions of ANNs, where smooth non-linearity functions such as sigmoid were used within hidden layers, the vanishing gradient problem (Hochreiter et al, 2001; Schmidhuber, 2015) meant that practical networks could not be more than a few layers in depth. Current state of the art ANNs obtain non-linearity through piecewise linear functions (Glorot et al, 2010) and enable many more layers before the vanishing gradient problem becomes an issue. While theoretical work has shown successes with as many as 10,000 layers (Xiao et al, 2018), most ANNs use around 100 layers or less. Even Chat GPT-3 only uses 96 layers (Brown et al, 2020).

Another problem with a single-iteration processing architecture is that its fixed depth implies a trade-off between the maximum complexity that the architecture can handle and the cost of training in order to cater for the average complexity of situations that the agent must cope with. Additionally, if we consider that such processing may entail multiple stages of processing, the order in which those stages is executed is fixed.

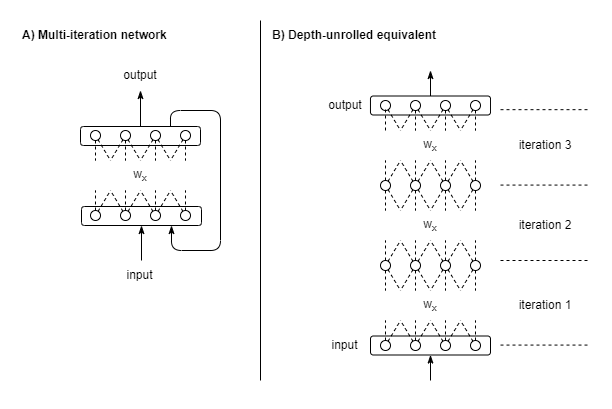

An architecture that employs multiple passes through its network can be conceptualised by unrolling its iterations into a much deeper single-iteration network, as illustrated in the diagram below. But the multi-iteration architecture has a number of advantages. Its depth varies dynamically as needed, for example that it is deeper for more complex problems. If processing is made up of multiple separable stages, the order in which those stages are executed can now be dynamically varied. It is additionally quite natural to imagine that for certain problems, some stages will be simply omitted entirely.

- Multi-iteration network. Panel A: a multi-iteration network with the result from its output layer fed back as input. Panel B: an equivalent single pass network by unrolling the iterations into a deeper network assuming 3 iterations. Notice that in the depth-unrolled network, weights are shared between sections.

So, it can be said that there is a limit on the complexity that can be handled by a single pass through any computational process. While that computational process can be extended with more parameters, there are practical limitations to how much it can be extended. For embodied agents, this appears as a limit on the complexity of the environmental and of their own body that they can sufficiently model and respond to within a single processing iteration. In biological terms, this practical limit is manifested in terms of both the energy costs of larger brains and in terms of the time required to reach maturity of brain function.

To adapt to more complex environments, an embodied agent must employ multiple iterations of processing. This enables, for example, further analysis of the environment in order to better model its state; or further deliberation of alternative action plans before proceeding. In biology, this provides scope for evolutionary pressures to trade off between a more energy hungry complex brain and a simpler less energy intensive one that might take longer to reach a decision for more complex problems. van Bergen & Kriegeskorte (2020), and also Spoerer et al (2020), make the case that recurrency is indeed employed in biology for that very reason.

The term recurrency can mean many things because recurrency can occur at any level. For example, in the case of Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) as used within AI, recurrency occurs at the level of a single neuron in order to hold state. Thus I shall continue to use the term multi-iteration processing in order to avoid confusion about the level at which the recurrency occurs in the context of discussion.

II.3 State Trajectories in a Multi-iteration Processor

The course taken by an agent to get from a past state to its current state is its state trajectory. Analogous to the path taken by an agent while walking through a maze, the state trajectory describes the path of the agent through state space. Here the state space can refer to its possible locations in physical space, such as in the maze example, or to more abstract possible states, such as an encapsulation of all measurable aspects of the agent’s body parts.

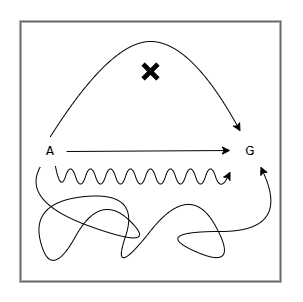

Not all state trajectories are good ones. The figure below illustrates a number of possible state trajectories from start state A to goal state G, while avoiding obstacle X. Each trajectory successfully reaches the goal, but they vary in other ways that may have significant impact to the agent. The length of the trajectory may indicate energy efficiency, which is important for an agent with limited energy reserves. The length may also indicate the time taken, which impacts whether or not the goal is reached “in time”. The smoothness of the trajectory can be important. A jagged trajectory might indicate that the agent’s physical body is moved in a chaotic way with abrupt stops and starts, causing damage to delicate moving parts from the stresses of that chaotic movement. A smoother trajectory may be easier for the agent to subsequently learn from and reason about in order to improve its later attempts; whereas a more chaotic path may add so much noise to the observations of the trajectory that the agent is unable to detect the most important patterns for such learning.

- Good and bad state trajectories. Examples of some possible state trajectories from start state A, to goal state G, while avoiding obstacle X. The shortest and smoothest trajectory is assumed to be the best: the most energy-efficient, the quickest, the least stresses applied to the mechanics of the agent.

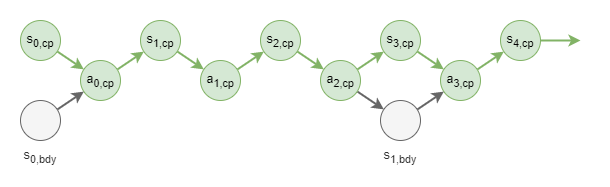

In a multi-iteration control process, there are periods where the controller traverses a state space that is independent of the state of the body that it controls, as illustrated below. It needs to incorporate mechanisms to control its own computational state. Those mechanisms are referred to as meta-management, because they relate to management of the controller’s own processes, rather than to management of the primary thing that the controller acts against (the agent’s body in this case).

- Control process trajectories. With multi-iteration processing, the control process (CP) has its own state trajectory (), influenced by its actions (). Control process actions only occasionally produce changes to body state ().

Within a learning setting, the control processes must learn to manage the state of the agent’s body. Typically this is influenced by feedback received in association with the outcome of some sequence of actions. That feedback must be interpreted and used to infer the best way to optimise the parameters of the control process. In a synthetic RL setting, that feedback and parameter optimisation is performed via hand-coded learning algorithms, often incorporating back-propagation and gradient descent. In a biological organism, the corresponding learning processes may be somewhat more complex and are certainly much less understood, but their effect is the same: that parameters of the control process are optimised such that future attempts would be more successful or efficient. This is a first concrete example of meta-management.

- Control Process with state. A control process (CP) that has state needs to act to manage its own state as well as the actions and state of the body that it controls. In some cases, this may require an additional meta-management process. Some interactions omitted from the diagram for simplicity.

The learning processes involved with a multi-iteration processor may be very similar to those involved with multi-step bodily actions. Each body action plays out over time, with complex dynamics affecting the speed and trajectory taken. The body actions required to reach a particular target body state may involve the sequencing and coordination of multiple actuators or muscles. Feedback about the relative success or failure may be sparse - only received as certain points in time, with no specific details about the relative effectiveness of steps in between, and even then the meaning of the information and how it relates to the state trajectory may be ambiguous. Any learning algorithm resolves that by assuming some distribution of the effects of the feedback over the length of the state trajectory and by averaging over multiple attempts. Some of the feedback received by an agent can be more frequent and detailed, such as endogenous feedback produced by evolved low-level mechanisms that encourage smooth and efficient movements.